Most scientists are convinced that liquid water is essential to understanding the way glacial ice behaves. Something that has a direct influence on the planet's climate. It is known, for example, that meltwater lubricates the gravel bases of glaciers and accelerates their march towards the sea. In recent years, various investigations in Antarctica have discovered, within the ice itself, hundreds of lakes and liquid rivers interconnected by an intricate network of channels. And they have also revealed the presence of large sediment basins just beneath the ice, which could contain the largest water reservoirs of all. But so far no one has been able to confirm the presence of large amounts of liquid water in these underground sediments, nor to study how they could interact with the ice itself.

Most scientists are convinced that liquid water is essential to understanding the way glacial ice behaves. Something that has a direct influence on the planet's climate. It is known, for example, that meltwater lubricates the gravel bases of glaciers and accelerates their march towards the sea. In recent years, various investigations in Antarctica have discovered, within the ice itself, hundreds of lakes and liquid rivers interconnected by an intricate network of channels. And they have also revealed the presence of large sediment basins just beneath the ice, which could contain the largest water reservoirs of all. But so far no one has been able to confirm the presence of large amounts of liquid water in these underground sediments, nor to study how they could interact with the ice itself.

Now, an international team of researchers has managed, for the first time, to locate a huge groundwater system actively circulating through deep sediments in West Antarctica. In an article published today in Science, scientists say that such systems, probably very common in Antarctica, may have as yet unknown implications for how the frozen continent reacts to climate change, or possibly even how it contributes to it.

"Many have hypothesized that there could be deep groundwater in these sediments," said Chloe Gustafson of Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and lead author of the paper, "but until now no one had obtained detailed images. The amount of groundwater we found is so significant that it probably influences ice stream processes. “Now we have to find out more and figure out how to incorporate that into existing models.”

The importance of groundwater

For decades, numerous researchers have flown over the Antarctic ice sheet to obtain subsurface characteristics from the air with their radars. Among many other things, those missions revealed the existence of sediment basins sandwiched between ice and bedrock. But with some exceptions, the aerial survey is only capable of showing the approximate contours of the basins, and says nothing about the water content and other important characteristics.

In one such exception, a 2019 study of the McMurdo Dry Valleys used helicopter-borne instruments to document a few hundred meters of subglacial groundwater beneath about 350 meters of ice. Very little, considering that most of Antarctica's known sedimentary basins are much deeper and most of its ice is much thicker, beyond the reach of aerial instruments.

In other places, researchers have drilled through the ice into the sediments, but have only managed to penetrate the first few metres. Therefore, current models of ice sheet behavior include only surface hydrological systems, which are within or just below the ice. This constitutes a significant handicap, since most of Antarctica's sedimentary basins are below current sea level, wedged between land ice attached to the bedrock and floating shelves of sea ice that border the continent. They are believed to have formed on the seabed during warm periods when sea levels were higher. If this were the case and the ice shelves retreated with a warmer climate, ocean waters could invade the sediments again, and the glaciers behind them could advance and raise sea levels around the world.

A map of the underground

In the new study, the researchers focused on the Whillans Ice Stream, just over 96 km wide, one of half a dozen fast-moving streams that feed the Ross Ice Shelf, the world's largest, almost as large as as big as the Iberian Peninsula. According to Gustafson, "ice streams are important because they channel about 90 percent of Antarctica's ice from the interior to the margins."

Previous research there has already revealed the presence of a subglacial lake within the ice, and also a sedimentary basin extending beneath it. Shallow drilling into sediments (down to just about 30 cm) already showed that there was liquid water and a thriving community of microbes. But what lies below remained a mystery.

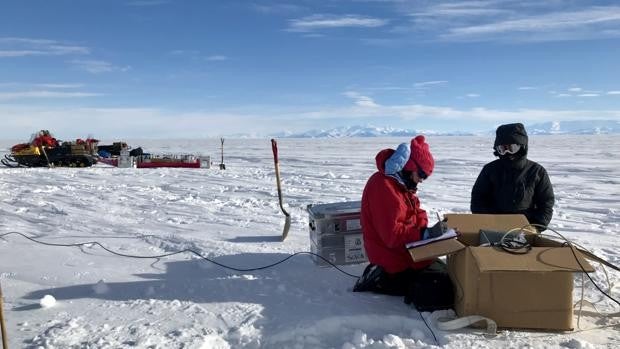

Trying to gather more data, in late 2018, a U.S. Air Force LC-130 ski plane dropped Gustafson, along with Lamont-Doherty geophysicist Kerry Key, into the area. Colorado School of Mines Matthew Siegfried and mountaineer Meghan Seifert in Whillans. Their mission: to better map sediments and their properties using geophysical instruments placed directly on the surface. Far from any help if something went wrong, for six grueling weeks the team dug in the snow, planted instruments and carried out countless other tasks.

On the ground, researchers used a technique called 'magnetotelluric imaging', which measures the penetration into the earth of natural electromagnetic energy generated high in the planet's atmosphere. Ice, sediment, fresh water, salt water, and bedrock conduct electromagnetic energy to different degrees; By measuring the differences, researchers can create maps of the different elements similar to those in an MRI. The team planted their instruments in snow pits for a day, then dug them up and relocated them, finally taking readings at about four dozen locations. They also reanalyzed natural seismic waves emanating from the earth that had been collected by another team, to help distinguish bedrock, sediment and ice.

Water in abundance

Their analyzes showed that, depending on location, the sediments extend below the base of the ice from half a kilometer to almost two kilometers before touching the bedrock. And they confirmed that the sediments are loaded with liquid water to the bottom. Researchers estimate that if it were all removed, it would form a water column 220 to 820 meters high, at least 10 times higher than in the shallow hydrological systems within and at the base of the ice, and perhaps even higher than that.

Saltwater conducts energy better than freshwater, so they were also able to show that groundwater becomes more saline with depth. Researchers think this makes sense, because the sediments are believed to have formed in a marine environment a long time ago. Ocean waters probably last reached what is now the area covered by Whillans during a warm period about 5,000 to 7,000 years ago, saturating the sediments with salt water. When the ice moved forward again, fresh melt water produced by pressure from above and friction at the base of the ice was evidently forced into the upper sediments, and probably continues to seep and mix today.

Gustafson and his team believe that this slow drainage of freshwater into the sediments could prevent water from accumulating at the base of the ice. Which could act as a brake on the forward movement of the ice. Measurements by other scientists at the ice stream's grounding line, the point where the land ice stream meets the floating ice shelf, show that the water there is somewhat less salty than seawater. normal. And that suggests that freshwater is flowing through the sediments into the ocean, making room for more meltwater to enter and keeping the system stable.

Potential risks

However, that stability could only be temporary. If the ice cover thinned, a distinct possibility as the climate warms, the direction of water flow could reverse. Overlying pressures would decrease and deeper groundwater could begin to well up toward the base of the ice. This could further lubricate the base of the ice and increase its forward movement. (The Whillans already moves ice seaward about a meter per day, very fast for glacial ice.) Additionally, if deep groundwater flows upward, it could transport geothermal heat naturally generated in the bedrock; This could further thaw the base of the ice and propel it forward. But whether that will happen, and to what extent, is unclear.

"Ultimately," says Gustafson, "we don't have much data on the permeability of sediments or how quickly water will flow. Would it make a big difference if it could generate an uncontrolled reaction? "Or is groundwater a supporting player in the grand scheme of ice flow?"

Furthermore, the known presence of microbes in shallow sediments adds another problem, the researchers say. It is likely that this basin and others are inhabited below; and if groundwater starts moving upward, it would take out the dissolved carbon used by these organisms. Lateral groundwater flow would send some of this carbon to the ocean. And that would possibly make Antarctica a hitherto overlooked source of carbon in a world where carbon is already too much. But again, Gustafon said, the question is whether or not this would be able to produce any significant effect.