The location of a point on the surface of our planet, or of the Earth in the universe, has been one of the essential drivers of scientific progress. This is the so-called "Longitude Problem," whose resolution, at the end of the 18th century, made it possible to precisely locate any location anywhere on the globe. After the Scientific Revolution, nothing was the same: the vision of man's relationship with nature changed, the foundations for the subsequent Industrial Revolution were laid, and the West strengthened its dominance of trade routes, eventually enabling the construction of the colonial empires of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The location of a point on the surface of our planet, or of the Earth in the universe, has been one of the essential drivers of scientific progress. This is the so-called "Longitude Problem," whose resolution, at the end of the 18th century, made it possible to precisely locate any location anywhere on the globe. After the Scientific Revolution, nothing was the same: the vision of man's relationship with nature changed, the foundations for the subsequent Industrial Revolution were laid, and the West strengthened its dominance of trade routes, eventually enabling the construction of the colonial empires of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

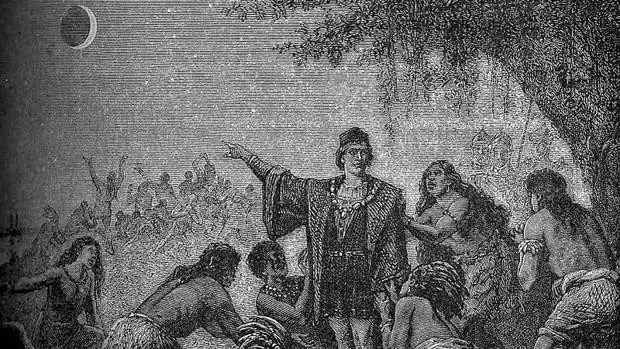

The 'Problem of Longitude' is part of a much more complex discipline: cosmography, a science that combined geography and astronomy, and whose objective was to understand our environment from a broad perspective. This process has its roots in the beginning of civilization and possibly in our very essence: the need to explore, to know, to understand. The first steps in this intellectual adventure were taken in Mesopotamia, in the early cultures of the Middle East, to which we owe so much, before being developed by Greece and Rome from a new rational perspective. Science emerged then, but not as an isolated tool, but as part of philosophy. The Middle Ages, unfairly underrated, allowed for a restructuring of cosmographic knowledge, partly distilled by Islamic civilization. Spain, in al-Andalus, played a pivotal role then, but also in the so-called Age of Discovery, beginning in the 14th century, along with Portugal. The two Iberian nations accomplished a series of extraordinary feats, expanding not only the geographical horizon by connecting distant and unknown lands to the West, initiating the first globalization, but also setting in motion a shift in perspective regarding humanity's position in the cosmos, a process reinforced by the Renaissance, a pan-European cultural movement that began on the Italian peninsula.

Scientific and technical innovations, informed by knowledge recovered from Greco-Roman antiquity, enabled, among many other astonishing feats, the first voyage that circumnavigated the globe. This voyage, begun in 1519 by Fernão de Magalhães, a navigator of Portuguese origin, was completed by Juan Sebastián Elcano in 1522, under the auspices of Emperor Charles V, King of Spain. A feat, incidentally, whose institutional celebration leaves much to be desired. Any other country would have been far more generous with an event that certainly contributed to changing the face of the world and consolidating Iberian dominance of trade routes across the oceans.

The International Astronomical Union, an organization founded in 1919, recently awarded me the prize for the best doctoral thesis in the 'Division C Education, Outreach and Heritage' category. My work, entitled 'Cosmography: The Science of the Two Orbs' and supervised by Dr. Marga Box Amorós, was presented at the University of Alicante last year in its Philosophy and Literature program.

It analyzes this entire process comprehensively and highlights Iberian contributions to science, especially up to the 18th century, when various governments invested substantially in maintaining and expanding knowledge. But it goes much further (not for nothing is the Spanish motto "Plus Ultra") and shows that cosmography, interpreted from a modern perspective, continues to play an essential role in our lives. Exploration continues, both within and beyond the Solar System, with the discovery of extrasolar planets, and attempts to exploit resources are also still present.

Cosmography, and science in general, continues to articulate our reality. Properly managed, knowledge is a source of well-being, but a society that forgets this fact and also its history is doomed to fall behind, allowing others to take advantage of the opportunities.

David Barrado is a professor of Astrophysics Research at the INTA-CSIC Astrobiology Center.