430,000 years ago, around thirty individuals, including men, women and children, wandered from here to there looking for a life in what is now the Burgos mountain range of Atapuerca. Robust, muscular and good runners, they cooperated to hunt bison, competed for prey on an equal footing with lions, wolves or panthers and violently confronted other groups. They must have known stress very well because any given day was a penance. Traumatic deaths, illness and pain were frequent, as reflected in the fossils found, but the remains themselves also speak of episodes of cooperation, compassion and dialogue—it has been shown that they spoke—attributes of an undeniable humanity.

430,000 years ago, around thirty individuals, including men, women and children, wandered from here to there looking for a life in what is now the Burgos mountain range of Atapuerca. Robust, muscular and good runners, they cooperated to hunt bison, competed for prey on an equal footing with lions, wolves or panthers and violently confronted other groups. They must have known stress very well because any given day was a penance. Traumatic deaths, illness and pain were frequent, as reflected in the fossils found, but the remains themselves also speak of episodes of cooperation, compassion and dialogue—it has been shown that they spoke—attributes of an undeniable humanity.

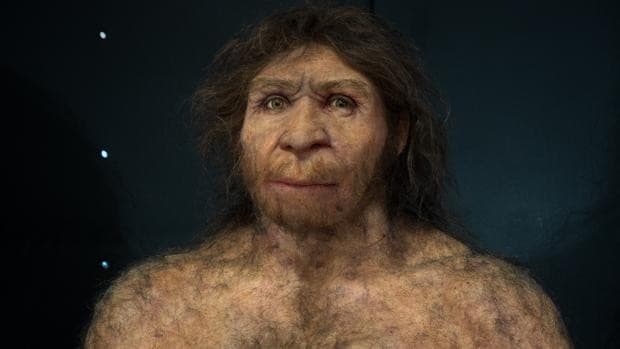

The most famous of the tribe is, without a doubt, Miguelón, as Skull 5, found thirty years ago in the Sima de los Huesos, is popularly known. Attributed to Homo heidelbergensis, ancestor of the Neanderthals, it is exhibited in the Museum of Human Evolution of Burgos. Recently, as a novelty, its seven cervical vertebrae have been added. The fossil skull is the most complete in the world and one of the most important pieces to understand how the first hominids that inhabited Europe lived, but it still holds the mystery of how its owner died. There are two versions found, with supporters and detractors, but equally exciting.

The hit

The first, defended for a long time, begins with a punch, a crash, a stone. Miguelón receives a very strong blow, perhaps from a fall or from a fellow man with bad intentions, on the left side of his face. The mamporro "caused the crushing of the maxillary bone and affected the dental socket, so that a tooth broke, became infected and led to septicemia, an infection caused by the outbreak of bacteria in the bloodstream," explains Ana Gracia Téllez, veteran researcher in the Sima de los Huesos. In his opinion, that could have been the cause of death. "These types of infections are serious and potentially fatal, and they get worse very quickly," says this renowned expert in anatomical reconstruction.

The blow left Miguelón in shock. "Probably, he broke the cartilage of his nose, his lip, the tear duct area..." explains Gracia. Furthermore, between dental plaque, gingivitis, abscesses and wear and tear—another gateway to bacteria—the poor hominid must have had terrible breath.

The agony

The martyrdom was prolonged. Due to the characteristics of the broken tooth, rounded in the chewing area, researchers believe that Miguelón suffered a lot for a long time, perhaps even years, before dying after the age of 45. It is possible that he tried to relieve himself with herbs used as sedatives, but finally the infection got the better of him. His imposing corpulence – it is believed that an average H. heidelbergensis reached 1.70 meters in height and weighed up to 100 kilos of pure muscle – did not help him much.

Skull 5, exhibited with the seven vertebrae in the Museum of Human Evolution of Burgos

–

Javier Trueba

But there is a second hypothesis about Miguelón's death. A more controversial one, which points to the attack of an animal. Some enigmatic marks on the back of the neck have recently been recognized as the paw of a bear, although it is not known if they were produced before or after the death of the hominid. For paleontologist Ignacio Martínez Mendizábal, a good expert on the fossil, it is very plausible that they were the cause of death. «That is my hypothesis. I think the type of marking fits better with bear attacks on living people than with what a bear might do to a dead body. But we still have to study it,” he says.

In addition to the phlegmon and claw marks, Miguelón "has a hole in his skull that could have been caused by a sharp object, that is, the peak of a stone or something like that. It is known that during his life he received many blows to the head, not fatal, although they reflect the rugged nature of his daily life. In short, he led a dangerous and possibly violent existence, so he died from some trauma, surely of human origin," says Juan Luis Arsuaga, his opinion on the Atapuerca site.

That violent and dangerous life was that of the rest of the members of his tribe. A recently published investigation documents up to 57 cranial injuries with signs of healing in the Sima individuals, which reveals that they had to occur before death.

In the majority of the specimens (17 of 20) cranial injuries caused by blunt blows appear. It didn't matter if they were male or female, adults or children. In nine of them the impacts were lethal. Scientists believe they were done intentionally, in violent attacks.

Very personal

Robust. The average height of a male of his species was 1.70 meters and he weighed between 90 and 100 kilos, without any fat.

Hunter-gatherer. He knew how to hunt in groups. He was after bison, deer and horses. It shared habitat with lions, hyenas, elephants, rhinos, wolves and bears.

Skilled. He could carve the stone in a complex way (Mode 2).

Name. Miguelón, in honor of the cyclist Miguel Indurain.

out of compassion

Stories of ferocity and cruelty may make us see these pre-Neanderthals as beasts, but that would be an unfair judgment. As far as is known, they were the first to show compassion, an intrinsically human behavior that, contrary to what was believed, appeared relatively early in our lineage.

And Miguelón did not suffer alone. During his convalescence from the infection, he necessarily received the group's help to survive, since pain of that caliber would barely have left him the strength to go out in search of food. “Someone had to provide it,” says Gracia.

Another relevant example of solidarity between these hominids is that of Benjamina, a girl who managed to live for eleven years with a serious cranial pathology that left her incapacitated. If no one had cared about her, she wouldn't have reached that age.

Furthermore, as Martínez Mendizábal explains, Miguelón was capable of speaking, which brings him even closer to us. "The first human species that heard like us is that of Miguelón, which means that it could produce the same sounds and that it surely spoke," he points out. «It resonated the same way. If Miguelón started talking, we wouldn't understand what he was saying, but we would immediately realize that it wasn't a monkey, but a person," he adds.

Researchers believe that Skull 5 will continue to provide new surprises in the future, at the same time that analysis techniques become more precise. "A fossil is a mine of information, it is never exhausted," they say. Maybe then we will know who or what killed the man from Atapuerca.

What if it was actually a woman?

Miguelón is normally represented as a corpulent man, a very macho guy, well covered in hair, with marked muscles. At first he was considered a male individual, but the truth is that his gender is not entirely clear. "It happens with some frequency in fossils, since sexual dimorphism (the differences between the two sexes) in the human skeleton is not great," explains Martínez Mendizábal. The problem is that Skull 5 shows some traits common to males, but at the same time it is one of the smallest in the Sima de los Huesos, which could indicate that it belonged to a female. In the absence of fossil DNA in the bones—finding them is extremely complicated—future research can use tooth enamel analysis techniques to try to solve the enigma. "I am sure that we will end up knowing Miguelón's true sex in the coming years, I have no doubt," says the researcher. Knowing whether the specimen was a man or a woman "makes it even more human, but it is anecdotal. Enter the catalog of curiosities. Perhaps, yes, the name should be changed.