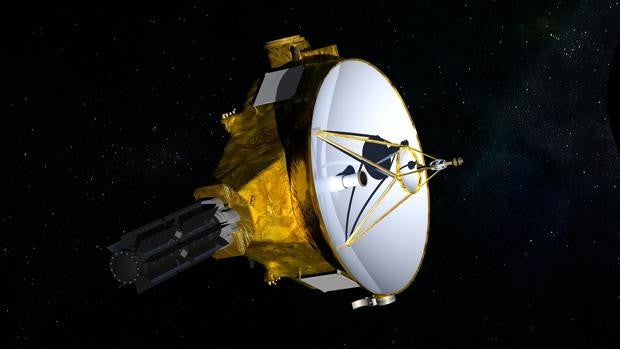

Weeks after NASA's New Horizons probe blasted off from home in early 2006, it took only a few minutes to send and receive messages from Earth. But as the spacecraft traveled further away, the minutes of communication turned into hours. And on April 17, it became the fifth spacecraft to reach within 50 astronomical units of the Sun, or 50 times farther from our star than Earth itself, more than 7.5 billion kilometers.

Weeks after NASA's New Horizons probe blasted off from home in early 2006, it took only a few minutes to send and receive messages from Earth. But as the spacecraft traveled further away, the minutes of communication turned into hours. And on April 17, it became the fifth spacecraft to reach within 50 astronomical units of the Sun, or 50 times farther from our star than Earth itself, more than 7.5 billion kilometers.

Although it's not the first time this has been achieved (the Voyager 1 and 2 probes and Pioneer 10 and 11 did), it's a milestone: reaching this remote region means communications are delayed by up to seven hours, even when information travels at the speed of light. And the wait doesn't end there: it takes another seven hours to know if Earth has received the message. And vice versa.

“It’s hard to imagine something so far away,” says Alice Bowman, New Horizons mission operations manager at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. “One thing that makes this distance tangible is how long it takes us on Earth to confirm that the spacecraft received our instructions. That went from almost instantaneous to now on the order of 14 hours. It makes the extreme distance real.”

To celebrate this incredible record, New Horizons—which aims to explore Pluto, its satellites, and asteroids in the Kuiper Belt—recently photographed the star field from the Kuiper Belt, at the edge of the Solar System, where one of its long-distance companions, Voyager 1, could be 'seen' in the background in a snapshot that had never been taken before.

Although Voyager 1 is too faint to be seen directly in the image, its location is precisely known thanks to NASA's radio tracking. This is how, on December 25, New Horizons was able to point to the space where Voyager 1 (circled in yellow) is located. Voyager 1 has become the most distant human-made object and the first spacecraft to leave the solar system (which was 18 billion kilometers away from New Horizons at the time). As for the bright spots, most are stars, but those that appear blurry are actually distant galaxies.

Image taken from New Horizons on December 25, 2020. In the yellow circle is Voyager 1, which is not visible to the naked eye in the photograph.

–

NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Southwest Research Institute

“To me, it’s a hauntingly beautiful image,” says Alan Stern, New Horizons principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. “Flying a spacecraft across our entire solar system to explore Pluto and the Kuiper Belt has never been done before. But since its launch nearly two decades ago, our children have grown up and we’ve grown older. And along the way, we’ve also made many scientific discoveries, inspired many scientific careers, and even made a little bit of history.”

In fact, New Horizons was designed to make history: traveling at 58,500 kilometers per hour, it is the fastest spacecraft ever created. Its gravity-assisted flyby of Jupiter in February 2007 not only shaved approximately three years off its journey to Pluto, but also allowed it to obtain the best views of Jupiter's faint ring and capture the first movie of an erupting volcano anywhere other than Earth.

New Horizons successfully conducted the first exploration of the Pluto system in July 2015, followed by the most distant flyby in history, and the first close-up look at a Kuiper Belt Object (KBO), with its flyby past Arrokoth on New Year’s Day 2019. From its unique position in the Kuiper Belt, New Horizons is making observations that can’t be made from anywhere else; even the stars look different from the spacecraft’s vantage point.

New Horizons team members are using giant telescopes like Japan's Subaru Observatory to scan the skies for another potential flyby target. Meanwhile, the spacecraft's systems are kept in tip-top shape, gathering data on the solar wind and the space environment in the Kuiper Belt, where it will remain active until the late 2030s. Long live New Horizons.