One of London's current tourist attractions is the cosmopolitan Soho neighborhood: there coexist small shops with department stores, theaters and concert halls, restaurants of all kinds and places, and bars that open "all day long." A carefree and happy place where flowing dresses of all colors wave like flags in hundreds of shop windows. But it wasn't always such a "chic" place. In the middle of the 19th century, the population, mostly poor immigrants, lived in close proximity and surrounded by the only vapor of their own filth. The city was growing at a rapid pace. So much so that there were no adequate infrastructures to prevent something as basic as the water they ingested and the excrement they expelled from mixing. And this is how a dirty diaper was the origin of the worst cholera epidemic that the British capital suffered. Although also the best breeding ground for a strange couple formed by a priest and an anesthesiologist to shake the foundations of the progress of modern civilization.

One of London's current tourist attractions is the cosmopolitan Soho neighborhood: there coexist small shops with department stores, theaters and concert halls, restaurants of all kinds and places, and bars that open "all day long." A carefree and happy place where flowing dresses of all colors wave like flags in hundreds of shop windows. But it wasn't always such a "chic" place. In the middle of the 19th century, the population, mostly poor immigrants, lived in close proximity and surrounded by the only vapor of their own filth. The city was growing at a rapid pace. So much so that there were no adequate infrastructures to prevent something as basic as the water they ingested and the excrement they expelled from mixing. And this is how a dirty diaper was the origin of the worst cholera epidemic that the British capital suffered. Although also the best breeding ground for a strange couple formed by a priest and an anesthesiologist to shake the foundations of the progress of modern civilization.

This is the premise that the scientific popularizer Steven Johnson uses in his work "The Phantom Map" (reissue now rescued in Spanish by Captain Swing), in which he presents us with a London on the verge of collapse due to its own waste: from the figure of the latrine cleaner, who was dedicated to literally removing feces from the antiquated sewage system, to the nauseating smell caused by the discharges thrown uncontrollably into the Thames, which in 1858 caused the phenomenon known as "The Great Stink." Thus, when in the last days of August 1854 the Lewis baby fell ill - we would now know him as patient zero - and his mother cleaned his diapers in a cesspool near the busy and well-regarded fountain on Broad Street - it was said that his water was the highest quality in the area, so many people traveled expressly from other parts of the city - dozens of deaths were recorded in a matter of hours throughout the Soho neighborhood.

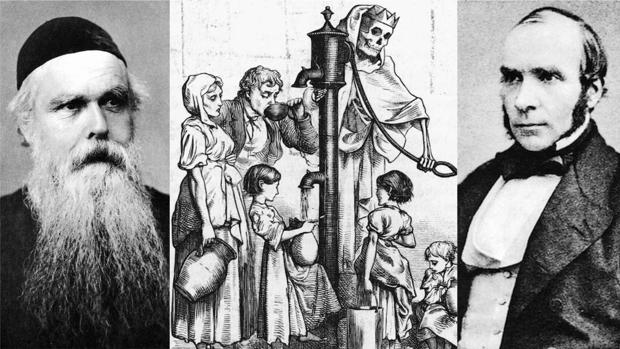

This is where a totally unexpected historical pairing comes into play: the renowned anesthetist John Snow and the folksy Reverend Henry Whitehead. Snow was a dry and taciturn doctor with his patients who, however, had earned the respect and admiration of the entire society of the time, by being one of the pioneers of modern anesthesia (he managed to assist in the delivery of the eighth child). of Queen Victoria). For his part, Whitehead was a young Anglican priest very attached to his community of St. Luke, on Berwick Street, very close to Soho Square, who knew the personal history of each of his parishioners by heart.

Science and patience

The anesthetist approached the problem with the eyes of a scientist: his intuition told him that there was a hidden explanation, a still invisible pattern that governed that virulent cholera outbreak, which left 616 dead in just one week. Snow had the idea that the disease was spread through water, contrary to what miasmatists thought, the most accepted current who was convinced that the disease was spread through bad odors - even the famous Florence Nightingale supported this theory vehemently in the writings of the time.

That is why he dedicated himself to visiting house to house in the neighborhood, asking patients and relatives about the origin of the water they had consumed - at that time, the theory that a living agent, called bacteria, was the cause was not even contemplated. of the disease, so the water could not simply be analyzed, as is currently the case. This is how he drew a map whose epicenter was the Broad Street fountain. On September 5, he managed, not without effort, to have the pump lever removed. From here, cases plummeted until the epidemic was considered under control. But even so, the scientific community still did not believe the anesthetist's approach.

Map created by Snow where each line is a dead person. You can see that most of them are piled up around the Baker Street pump. At first, Reverend Whitehead, after hearing Snow's theory, also disagreed. And to prove that the doctor was wrong, he began his own survey, much less methodical but including personal notes that were later revealed to be decisive. That's how he got to a cesspool located in the Lewis family's basement, where the baby's mother cleaned the diapers. When excavating the sinkhole, they discovered that, indeed, there were significant leaks that connected this well with the Broad Street sinkhole, convincing them that Snow - and not the miasmatics, as he himself thought - was right. The reverend gave Snow definitive evidence of his theory, confirming that it had not been a simple coincidence, but had proven causality.

This strange tandem, which, by the way, ended in friendship, laid the foundations for the control of the following cholera outbreaks. In addition, it served as motivation to reorient the sewage network, which from then on dumped waste away from the city. A lesson in how scientific evidence combined with local knowledge can stop an epidemic. Do these two concepts sound familiar to you?